WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY

JANUARY 18–25, 2017

PRAYER / WORSHIP: Homiletic Notes for the Week of Prayer

2 Corinthians 5:14-20

By Rev. Jan Schnell Rippentrop, PhD -Anticipated

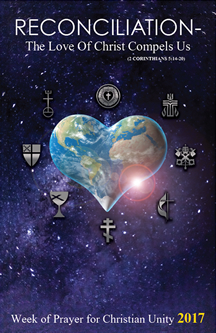

RECONCILIATION—THE LOVE OF CHRIST COMPELS US

2 Corinthians 5:14-20

¹⁴For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. ¹⁵And he died for all, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them. ¹⁶From now on, therefore, we regard no one from a human point of view; even though we once knew Christ from a human point of view, we know him no longer in that way. ¹⁷So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! ¹⁸All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation; ¹⁹that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us. ²⁰So we are ambassadors for Christ, since God is making his appeal through us; we entreat you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God.

The motivational force of these verses is palpable from the beginning and does not let up. These seven verses grip the hearer from their outset, where the love of Christ is the wellspring of action, and the text continues to captivate the hearer all the way to its conclusion, where love results in reconciliation with God and the world.

Even though the motivating power of love is clear from the outset, the Greek here is ambiguous. Does ἡ γὰρ ἀγάπη τοῦ Χριστοῦ, which is translated for the love of Christ, mean “Christ’s love” or does it mean “believers’ love for Christ?” Both are accurate renderings of the Greek phrase. It could well be that this ambiguity is precisely Paul’s intent: both are true at the same time—Christ’s love urges us on and our love for Christ urges us on.

If one looks at the wider Pauline corpus, one observes another interpretive cue. When Paul writes about love, Paul tends to present love as embodying a particular direction. Love, in Pauline literature, tends to move from God or Christ toward humans and the world. For example, Paul identifies, in Romans 8, God’s love in Christ as inexorably coming toward humanity. What is certain here in 2 Corinthians is that the love of which Paul speaks is neither nostalgic nor sappy. This is love on the move—love that goes forth as a mover and a shaker.

There is another trait of the Pauline understanding of love that is pertinent to the interpretation of this text. In Paul’s writings, God’s love does not simply remain a trait of God alone. God’s love goes forth from God and bears transformative power. We see such transformation in Galatians 5:6, where love is the catalyst that makes faith effective. We also see Paul’s concept of love as a transformative power in this passage. Here love urges us on to act in the world in ways resonant with the new thing God is doing. In this passage Paul tells the reader, as will be explored below, a particular way that human action can resonate with God’s love. Paul says that, when human action resonates with the risen life of Christ, it results in reconciliation.

CHRIST’S DEATH AS UNIFIER

As Paul tells it, reconciliation is hardly of human origin; rather, God generates reconciliation through the death and resurrection of Christ. Paul identifies Christ’s death as the very reason that love of Christ can urge us forward. That is, Christ’s death is foundational to love’s transformative movement in our lives.

At this point, Paul slows the narrative down—a sure sign in Pauline literature that a crucial point is being made. Paul painstakingly walks the reader step by step through his theological argument. How do we know that the love of Christ urges us on? Here is how we know:

- Christ died for all.

- If Christ stood in for all when he died, then all have died.

- Christ died for all in order that one is no longer bound to live in a manner that watches out primarily for oneself (e.g., in order to achieve the law).

- Christ died for all in order that one is now free to live for Christ, the crucified and risen one.

Why would Paul take the time to focus a literary zoom lens on this section? First and principally, Paul focuses in on this section because the cross of the crucified Christ is central to Pauline theology. Jesus’ death on the cross overcomes sin that keeps us separated from God and from the rest of creation, and Jesus’ death denounces the suffering that plagues the earth and all creatures. Christ’s death unifies by overcoming all that separates us from love and from loving. Secondly, this zoom lens makes clear that Christ’s great act of love (and our love of Christ) urge us on, i.e., free us up, to live for Christ. As we shall see, living for Christ involves living for the life of the world.

CHRIST’S RESURRECTED LIFE AS UNIFIER

In verse 16, Paul takes up the resurrection as his lens. To be certain, Paul maintains the inseparability of the Christ event—the death and resurrection are forever bound. Yet, here the point Paul makes is that it is no longer possible to view anyone as if the resurrection has not taken place. Every single thing has changed. All has been transformed through Christ’s death and resurrection. Christ’s life unifies the world by transforming all of creation into the new creation in light of the sure and certain hope of the resurrection. The transformation leaves not one thing unaltered because even the norms of judgment are altered. We can no longer regard anything “from a human point of view.”

At this point, we must pause to address one way this text has been misused in the past by exegetes and preachers. The problem arises when not regarding things from a human point of view meant that one should, then, regard things from a spiritual point of view. Hold on. We have not yet arrived at the problem; there is one more step. When the “spiritual point of view” was then taken to be a disembodied, ethereal state, the interpretation resulted in a specific problem: absenting oneself from the concrete problems of this world. This problematic abandonment of the world for the realm of the spiritual is a very difficult interpretation to support as a reader moves into the next verses. In the verses that follow, Paul advocates, not for absenting oneself from the world, but for reinvesting oneself in troublesome contexts of the world. He advocates for reinvesting oneself fitted with the reconciling hope of the crucified and risen Jesus Christ. He advocates for reinvestment when he transitions from “everything has been made new!” to Christ’s reconciling action toward humans and, then, to our “ministry of reconciliation.” Paul assures the Corinthians that living within the promise of everything being made new, i.e., living within the promise of the resurrection, and living with the resultant hope in the resurrection promise is in no way abstracted from the world. Instead, the result of resurrection hope is active participation in a ministry of reconciliation. Theologian Jürgen Moltmann writes, concerning the resurrection, that “human beings don’t have to try to cling to their identity through constant unity with themselves, but will empty themselves into non-identity, knowing that from this self-emptying they will be brought back to themselves again for eternity.”¹ Moltmann means that when one lives in resurrection hope, one does not need to strive to be personally or individually good enough. Instead, one participates in self-emptying, i.e., giving of oneself on behalf of another. Emptying oneself does not result in loss of the self as is sometimes feared; emptying oneself, given the power of the resurrection, results in coming into one’s most whole self.

RECONCILIATION: HUMAN RESPONSE TO CHRIST’S ACTS OF UNIFICATION

Verse 18 (and its echo in verse 19) tells us that Christ’s death and resurrection was anything but an abandonment of this world and its dire and destructive issues. Rather, the Christ event deeply invested Christ in the life of the world. Jesus’ death and resurrection intimately identified Christ with sin, suffering, and the deathly pain of creaturely existence. We see this very clearly if we expand our pericope by just one verse. We then hear Paul say, “For our sake [God] made him (i.e., Jesus) to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” Jesus so deeply invested himself among humans, Jesus so intimately identified with creation that he took on sin in order to free creation from sin.

It is important for the preacher to note that in verses 18-20, Paul uses “reconciliation” in a way that differs from his typical usage of the term. Paul tends, as seen in Romans, to connect reconciliation to justification. However, that is not what we see here. Here in 2 Corinthians, Paul uses reconciliation to talk about the mutual restoration of broken relationships. Maybe this change is due to the remarkably personal tone of 2 Corinthians. Certainly, Paul is addressing human patterns of behavior in families, friendships, and communities. When Paul implores the reader to “be reconciled,” he urges hearers toward actions of reconciliation within their social world. These acts of reconciliation occur in the world, for the life of the world because they are compelled by Christ’s love. Christ’s love is no fleeting fancy. Christ’s love is backed by the power of his death and resurrection that makes all things new.

Since this text urges human acts of reconciliation, we now take a closer look at what that entails by unpacking five principles of reconciliation and by examining what reconciliation may look like within religious assemblies and in daily lives that openly face the world.

5 Principles of Reconciliation

These are five principles of reconciliation drawn from 2 Corinthians 5:14-20.

- Reconciliation is God’s gift to creation.

Three things are important here. First, the reconciliation of which 2 Corinthians speaks is God’s reconciliation and is brought about by God’s power. The unique thing about this 2 Corinthians passage is the declaration that humans share in God’s work of reconciliation. Human reconciliation derives from God’s reconciliation. At the same time, this text witnesses to the fact that humans have agency to serve as reconcilers in an extension of God’s reconciling action. Secondly, reconciliation is a GIFT from God! It is a free and undeserved gift—unearned and uncontrollable and unconditional. Thirdly, God’s gift of reconciliation is for all of creation. Divine reconciliation is a gift, not only for humans, but for all of creation. - Reconciliation addresses pain.

God reconciled the world through Jesus Christ, says our text in verse 18. More specifically, God reconciled the world through the death and resurrection of Christ. There is nothing more painful and devastating than the God-forsakenness that Jesus experienced in his death. We in the church go wrong when we domesticate the impact of Jesus taking on humanity’s sin and suffering and turn it into stock phrases. When “he became sin who knew no sin” is a phrase that rolls right off the tongue, it is time to reassess. That is a gut-punch of a sentence—the kind that leaves you without enough air. Jesus suffered in order to reconcile the world to himself. Jesus died in order to reconcile the world. Reconciliation, for Jesus, was an active, whole body experience that demanded his life. Reconciliation, for us, is more than a philosophy with good theology behind it. Processes of reconciliation most likely include pain. - Reconciliation expends oneself on behalf of another.

Jesus did not need to reconcile the world for his own well-being. Jesus reconciled the world for the sake of the world. When we participate in acts of reconciliation, we do not act only in our own best interest; we reconcile for the sake of the other, for the sake of the world. One expends oneself on behalf of the other when one does the work of reconciliation. Actions that defy hatred require something of the giver. When we break down barriers, build bridges, make peace, and extend hospitality, we participate in acts of reconciliation in full knowledge that we will be changed through the encounter. - Reconciliation is proclaimed by doing.

Preachers will most congruently proclaim 2 Corinthians 5:14-20 by enacting reconciliation in the pulpit. What does this mean? First a caveat: reconciliation enacted in the pulpit is in addition to, not in place of, living a life and engaging in a whole ministry of reconciling actions. Enacting reconciliation in the pulpit entails doing reconciliation within preaching as opposed to merely talking about reconciliation. Doing reconciliation is more faithful to this text, not to mention more effective. This view does require a preacher to view words as capable of doing things. However, one doesn’t have to look far to see words at work doing things. Consider, for example, a city official’s pronouncement: “You must evacuate this town by 4pm today.” Whether townspeople evacuate or resist by staying, these words have done something. Our words do things; they can comfort, redirect, or absolve. We faithfully preach this text when we reconcile. What in your community needs reconciliation? How can you, through your sermon, let the assembly really feel reconciled? Remember two things: this approach is quite different than talking about reconciliation, and such a sermon will be one powerful step in a much larger process of reconciliation. - Reconciliation brings newness.

Verses 17-18 show that reconciliation through Christ brings about entirely new life. Jesus’ resurrection from the dead was not simply possible from that which already existed in the world. Jesus’ resurrection was the entirely new thing that God brought about. When God advents in the world, God characteristically brings about that which is entirely new.² God’s active involvement in the world means that, as we work toward reconciliation in the midst of the broken world that surrounds us, we can expect God to continue to act in these characteristic ways that bring new life, where previously we could see only death.

Reconciliation within Religious Assemblies

Worshipping assemblies can be sites of reconciliatory action. Worship ritually enacts realities of God’s presence, such as the reality of God’s gift of reconciliation. In praise and petition, in reading and proclamation, in bathing and feeding, in song and foretaste, the assembled people worship the crucified and risen Christ in whom they find reconciliation. Take “praise” for example. Assemblies praise Christ for reconciling the world to himself. Consider this ancient prayer of praise found in the Sacramentary of Sarapion of Thmuis in 4th Century Egypt: “Lover of humanity and lover of the poor, you are reconciled to all and draw all to yourself through the coming of your beloved Son.” Such praise of God’s reconciling action through Christ does not merely inform the assembly’s knowledge. Praise can actually form an assembly’s disposition toward God—practicing praise of God’s reconciling action can instill participants with adoration of God’s reconciling action.

Homiletical theologian Tom Long reflects on how practices form faith. He says that practices are those things that “Christians do together that not only express our faith but also shape our faith.”³

It is in doing the practices of the faith, such as praise and preaching, that Christians become most fully who they are. When assemblies regularly gather to praise God’s reconciling action, to petition God to reconcile, and to proclaim God’s redeeming reconciliation, then assemblies come to expect God’s reconciliation and to become reconcilers themselves.

Reconciliation in the World

Ethicist and Theologian Richard Perry, Jr. describes the Christian assembly in a different context from worship, that of public spaces where non-violent direct protest occurs for the sake of reconciliation. Perry describes the “practice of physicality,” by which he means “the act of intentionally placing one’s body into public spaces as a means of expressing concerns for justice in the world.”⁴ Perry claims that, for Christians, this “practice of physicality” is not arbitrary but is, instead, an attempt to imitate Christ by being physically present and performing actions in ways analogous to Christ’s presence, action and suffering. Practices of physicality are responses to actions initiated by God. In terms of our 2 Corinthians passage, “All this [new creation] is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation.” Christian’s who physically show up to be agents of reconciliation in the world are embedded within Christ’s practices of physicality in which he suffered death on the cross, rose bodily, and comes toward creation making all things new.

Christ’s message of reconciliation, Paul writes, has been entrusted to us. That means that God’s reconciling work, enacted through human hands, can be experienced in the midst of human history. It also suggests that each member of our assemblies is imbued with a vocational gift to proclaim God’s reconciliation to the world, using one’s action and voice.

People will carry out this vocation in a variety of ways. Many in 2017 will commit themselves to open, interreligious dialog about the effects of the Reformation. Reconciliatory dialog will courageously include conversation about both liberating and constricting effects of the Reformation. Reconciliatory actions will focus on mutual praise of God and mutual acts of justice in the world. Physical actions of reconciliation in the world are precisely what these verses from 2 Corinthians urge of the hearer.

Assemblies’ participation in “practices of physicality” puts them at sites where God manifests God’s reconciling presence to the world. God actively incites assemblies to live in the Spirit’s eschatological tenor. This occurs because God has performed the ultimate act of reconciliation through the death and resurrection of Christ. Therefore,

- Preachers notice where death or death-dealing practices have a hold in the world;

- Preachers recognize the new thing that God is doing in their midst;

- Preachers bear witness to the new thing God is doing.

Preaching proclaims reconciliation that can be known within the fabric of our daily lives. Preaching reconciliation proclaims the alleviation of suffering and the creation of life in the midst of death. Preaching 2 Corinthians 5 does not remove people from this world; instead it opens our eyes more fully to local realities because encounter with God through scripture orients one to God’s ways in the world.

Rev. Dr. Jan Schnell Rippentrop teaches homiletics at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago and serves as Director of the Master of Arts Programs. She did her doctoral work at Emory University, studying liturgical theology and homiletics. Most of her research revolves around the way God’s living Word is heard, which has led to specific research in pneumatology, political theology, and eschatology. In both her teaching and her research, she is committed to interdisciplinarity, theories that recognize the inherent value and wisdom that each participant brings. A conference speaker and preacher, she delights in God’s spirited movement in the fabric of our daily lives and on the streets of our public spaces.

Before Emory, Rippentrop served as pastor among the incredible people of Zion Lutheran Church in Iowa City, Iowa. Rippentrop holds an M.Div. from Wartburg Seminary. In addition to her teaching and research, she is also passionate about visual and performance arts, perennial gardening, sustainable practices, and slam poetry.

¹Jürgen Moltmann, The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 67.

²See, for example, Jürgen Moltmann’s Theology of Hope or The Coming of God.

³Thomas G. Long, “One Thing I Do Know: The Practice of Testimony,” Sermon preached at Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, March 1, 2015. http://www.fapc.org/worship/sermons/filterby/the+rev.+dr.+thomas+long , accessed 11.2015.

⁴Richard Perry, Jr., “Physicality as a New Model for Lutheran Ethics in a Multicultural Global Community” in Justification in a Post-Christian Society,eds. Carl-Henric Grenholm and Goran Gunner (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2014), 155.